2.4 — Costs of Production

ECON 306 • Microeconomic Analysis • Fall 2022

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/microF22

microF22.classes.ryansafner.com

Recall: The Firm's Two Problems

1st Stage: firm's profit maximization problem:

Choose: < output >

In order to maximize: < profits >

2nd Stage: firm's cost minimization problem:

Choose: < inputs >

In order to minimize: < cost >

Subject to: < producing the optimal output >

- Minimizing costs ⟺ maximizing profits

Production for Sale in a Competitive Market

- We assume (for now) the firm is in a competitive industry:

Firms’ products are perfect substitutes

Firms are “price-takers”, no one firm can affect the market price

Market entry and exit are free†

† Remember this — it turns out to be the most important feature that distinguishes different types of industries!

Profit

Recall that profit is: π=pqrevenues−(wl+rk)costs

We’ll first take a closer look at costs today

Next class we’ll put costs together with revenues to find optimal q∗ that maximizes π (the first stage problem)

Opportunity Costs in Production

Production Costs are Opportunity Costs

- Remember, economic costs are broader than the common conception of “cost”

- Accounting cost: monetary cost

- Economic cost: value of next best alternative use of resources given up (i.e. opportunity cost)

Production Costs are Opportunity Costs

This leads to the difference between:

- Accounting profit: revenues minus accounting costs

- Economic profit: revenues minus accounting + opportunity costs

A really difficult concept to think about!

Production Costs are Opportunity Costs

- Another helpful perspective:

- Accounting cost: what you historically paid for a resource

- Economic cost: what you can currently get in the market for a selling a resource (it’s value in alternative uses)

A Reminder: It's Demand all the Way Down!

Supply is actually Demand in disguise!

An (opportunity) cost to buy (scarce) inputs for production because other people demand those same inputs to consume or produce other valuable things!

- Price necessary to pull them out of other valuable productive uses in the economy!

Production Costs are Opportunity Costs

Because resources are scarce, and have rivalrous uses, how do we know we are using resources efficiently??

In functioning markets, the market price measures the opportunity cost of using a resource for an alternative use

Firms not only pay for direct use of a resource, but also indirectly compensate society for “pulling the resource out” of alternate uses in the economy!

Production Costs are Opportunity Costs

- Every choice incurs an opportunity cost

Examples:

- If you start a business, you may give up your salary at your current job

- If you invest in a factory, you give up other investment opportunities

- If you use an office building you own, you cannot rent it to other people

- If you hire a skilled worker, you must pay them a high enough salary to deter them from working for other firms

Opportunity Cost is Hard for People

Opportunity Costs vs. Sunk Costs

Opportunity cost is a forward-looking concept

Choices made in the past with non-recoverable costs are called sunk costs

Sunk costs should not enter into future decisions

Many people have difficulty letting go of unchangeable past decisions: sunk cost fallacy

Sunk Costs: Examples

Sunk Costs: Examples

Sunks Costs: Examples

Common Sunk Costs in Business

Licensing fees, long-term lease contracts

Specific capital (with no alternative use): uniforms, menus, signs

Research & Development spending

Advertising spending

The Accounting vs. Economic Point of View I

- Helpful to consider two points of view:

“Accounting point of view”: are you taking in more cash than you are spending?

“Economic point of view”: is your product you making the best social use of your resources

- i.e. are there higher-valued uses of your resources you are keeping them out of?

The Accounting vs. Economic Point of View II

Implications for society: are consumers best off with you using scarce resources (with alternative uses!) to produce your current product?

Remember: this is an economics course, not a business course!

- Economists are pro-market, not pro-business!

- What might be good/bad for one business might have bad/good consequences for society!

Consumer Sovereignty in a Market Economy

Ludwig von Mises

1881—1973

“The direction of all economic affairs is in the market society a task of the entrepreneurs. Theirs is the control of production. They are at the helm and steer the ship. A superficial observer would believe that they are supreme. But they are not. They are bound to obey unconditionally the captain's orders. The captain is the consumer. Neither the entrepreneurs nor the farmers nor the capitalists determine what has to be produced. The consumers do that. If a businessman does not strictly obey the orders of the public as they are conveyed to him by the structure of market prices, he suffers losses, he goes bankrupt, and is thus removed from his eminent position at the helm. Other men who did better in satisfying the demand of the consumers replace him.”

“The consumers patronize those shops in which they can buy what they want at the cheapest price. Their buying and their abstention from buying decides who should own and run the plants and the land. They make poor people rich and rich people poor. They determine precisely what should be produced, in what quality, and in what quantities,” (p.270).

von Mises, Ludwig, 1949, Human Action

Costs in the Short Run

Costs in the Short Run

- Total cost function, C(q) relates output q to the total cost of production C†

C(q)=f+VC(q)

Costs in the Short Run

- Total cost function, C(q) relates output q to the total cost of production C†

C(q)=f+VC(q)

- Two kinds of short run costs:

1. Fixed costs, f are costs that do not vary with output

- Only true in the short run! (Consider this the cost of maintaining your capital)

Costs in the Short Run

- Total cost function, C(q) relates output q to the total cost of production C†

C(q)=f+VC(q)

- Two kinds of short run costs:

1. Fixed costs, f are costs that do not vary with output

- Only true in the short run! (Consider this the cost of maintaining your capital)

2. Variable costs, VC(q) are costs that vary with output (notice the variable in them!)

- Typically, the more production of q, the higher the cost

- e.g. firm is hiring additional labor

† Assuming that (i) firms are always choosing input combinations that minimize total cost and (ii) input prices are constant. See more in today’s appendix.

Fixed vs. Variable costs: Examples

Example: Airlines

Fixed costs: the aircraft, regulatory approval

Variable costs: providing one more flight

Fixed vs. Variable costs: Examples

Example: Car Factory

Fixed costs: the factory, machines in the factory

Variable costs: producing one more car

Fixed vs. Variable costs: Examples

Example: Starbucks

Fixed costs: the retail space, espresso machines

Variable costs: selling one more cup of coffee

Fixed vs. Sunk costs

Diff. between fixed vs. sunk costs?

Sunk costs are a type of fixed cost that are not avoidable or recoverable

Many fixed costs can be avoided or changed in the long run

Common fixed, but not sunk, costs:

- rent for office space, durable equipment, operating permits (that are renewed)

When deciding to stay in business, fixed costs matter, sunk costs do not!

Cost Functions: Example

Example: Suppose your firm has the following total cost function:

C(q)=q2+q+10

Write a function for the fixed costs, f.

Write a function for the variable costs, VC(q).

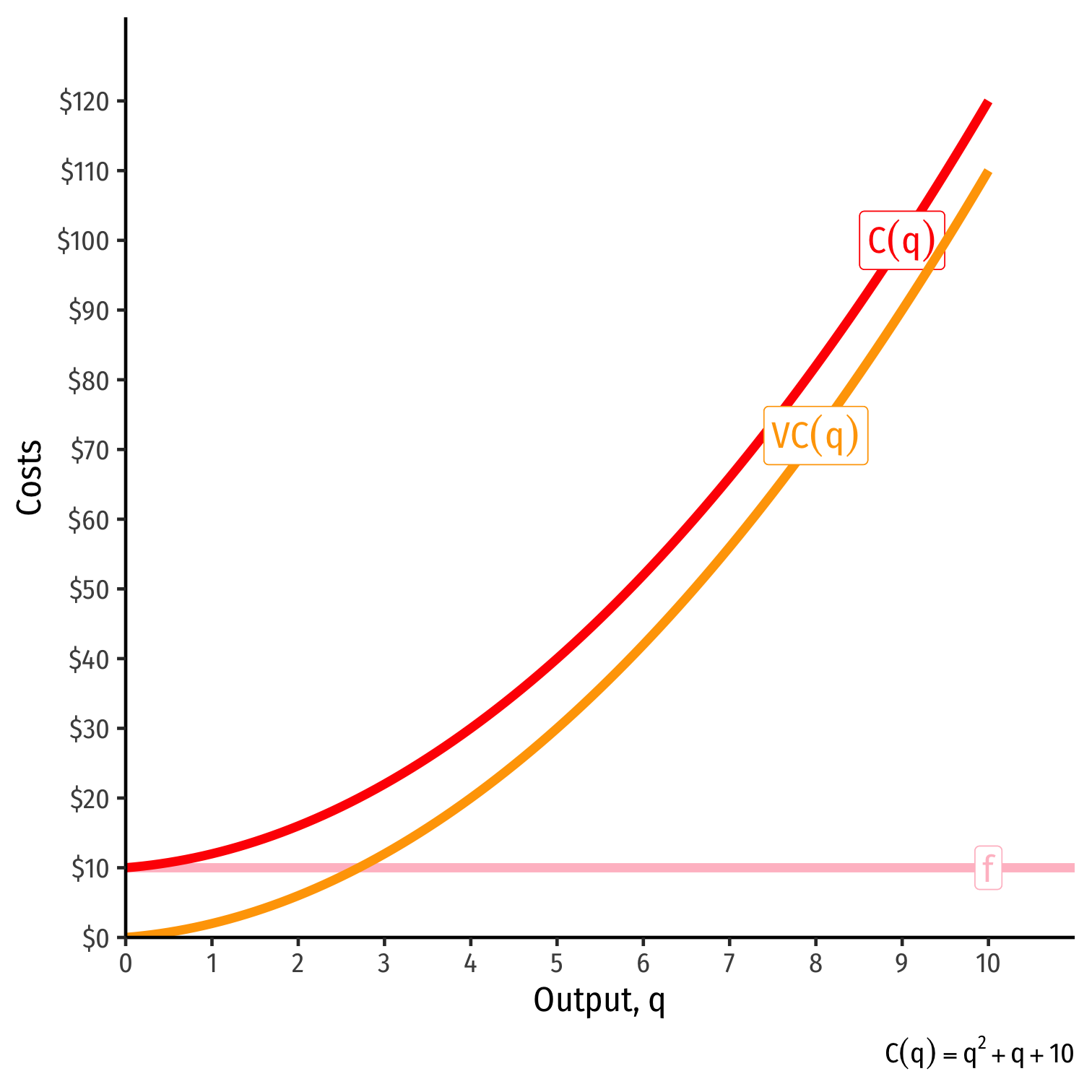

Cost Functions: Example, Visualized

| q | f | VC(q) | C(q) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 1 | 10 | 2 | 12 |

| 2 | 10 | 6 | 16 |

| 3 | 10 | 12 | 22 |

| 4 | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| 5 | 10 | 30 | 40 |

| 6 | 10 | 42 | 52 |

| 7 | 10 | 56 | 66 |

| 8 | 10 | 72 | 82 |

| 9 | 10 | 90 | 100 |

| 10 | 10 | 110 | 120 |

Average Costs

- Average Fixed Cost: fixed cost per unit of output:

AFC(q)=fq

Average Costs

- Average Fixed Cost: fixed cost per unit of output:

AFC(q)=fq

- Average Variable Cost: variable cost per unit of output:

AVC(q)=VC(q)q

Average Costs

- Average Fixed Cost: fixed cost per unit of output:

AFC(q)=fq

- Average Variable Cost: variable cost per unit of output:

AVC(q)=VC(q)q

- Average (Total) Cost: (total) cost per unit of output:

AC(q)=C(q)q

Marginal Cost

- Marginal Cost is the change in total cost for each additional unit of output produced:

MC(q)=ΔC(q)Δq

Calculus: first derivative of the cost function

Marginal cost is the primary cost that matters in making decisions

- All other costs are driven by marginal costs

- This is the main cost that firms can “see”

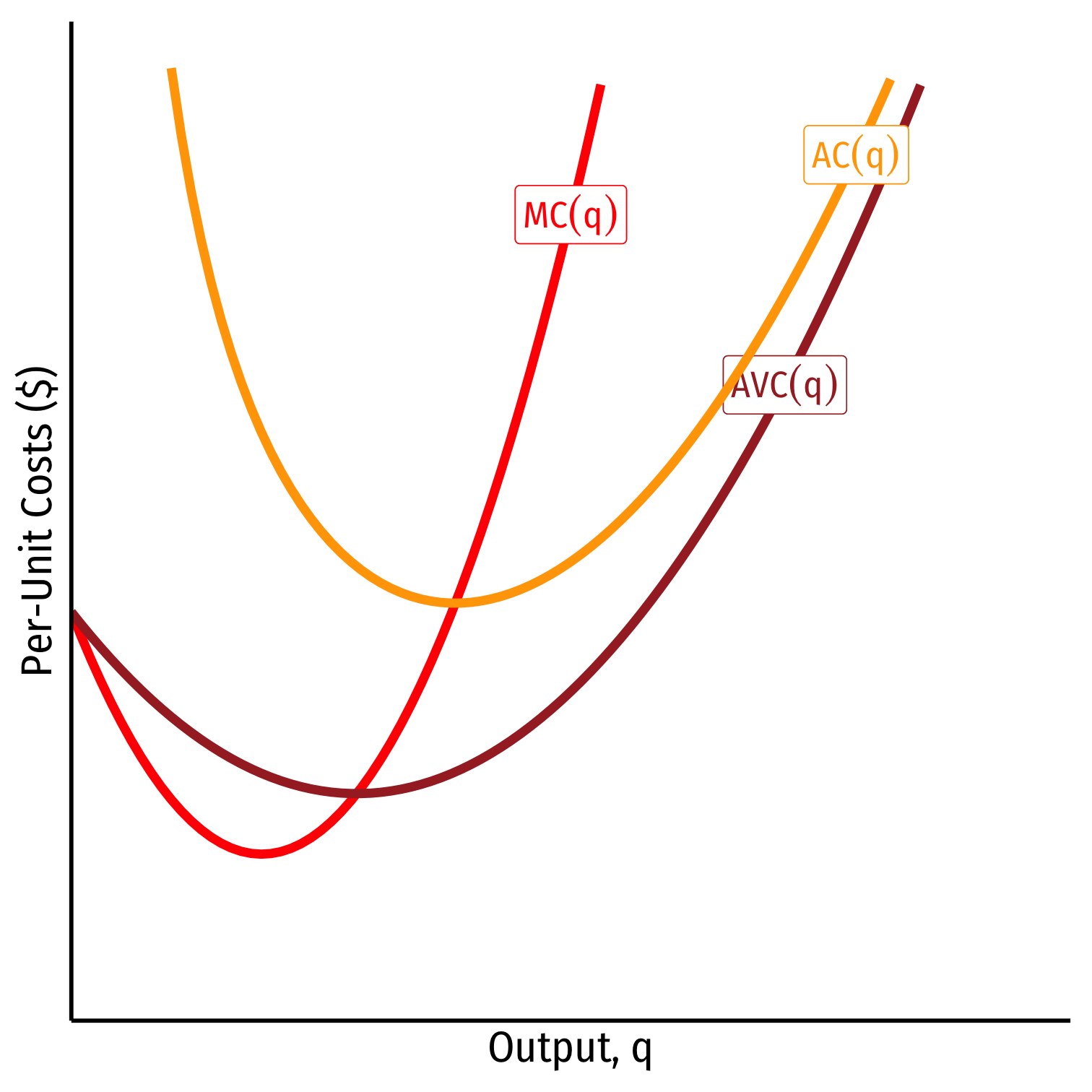

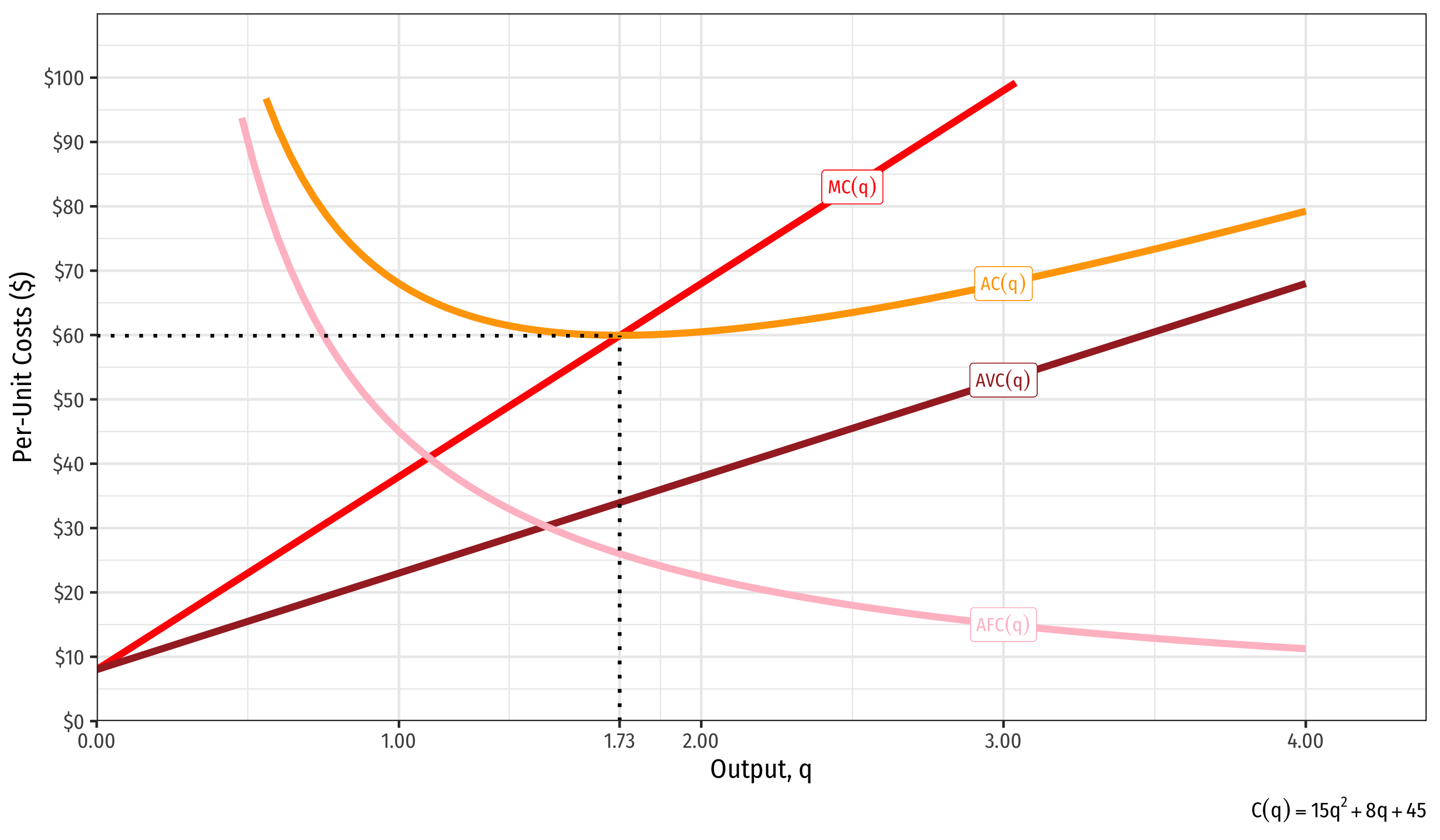

Average and Marginal Costs: Visualized

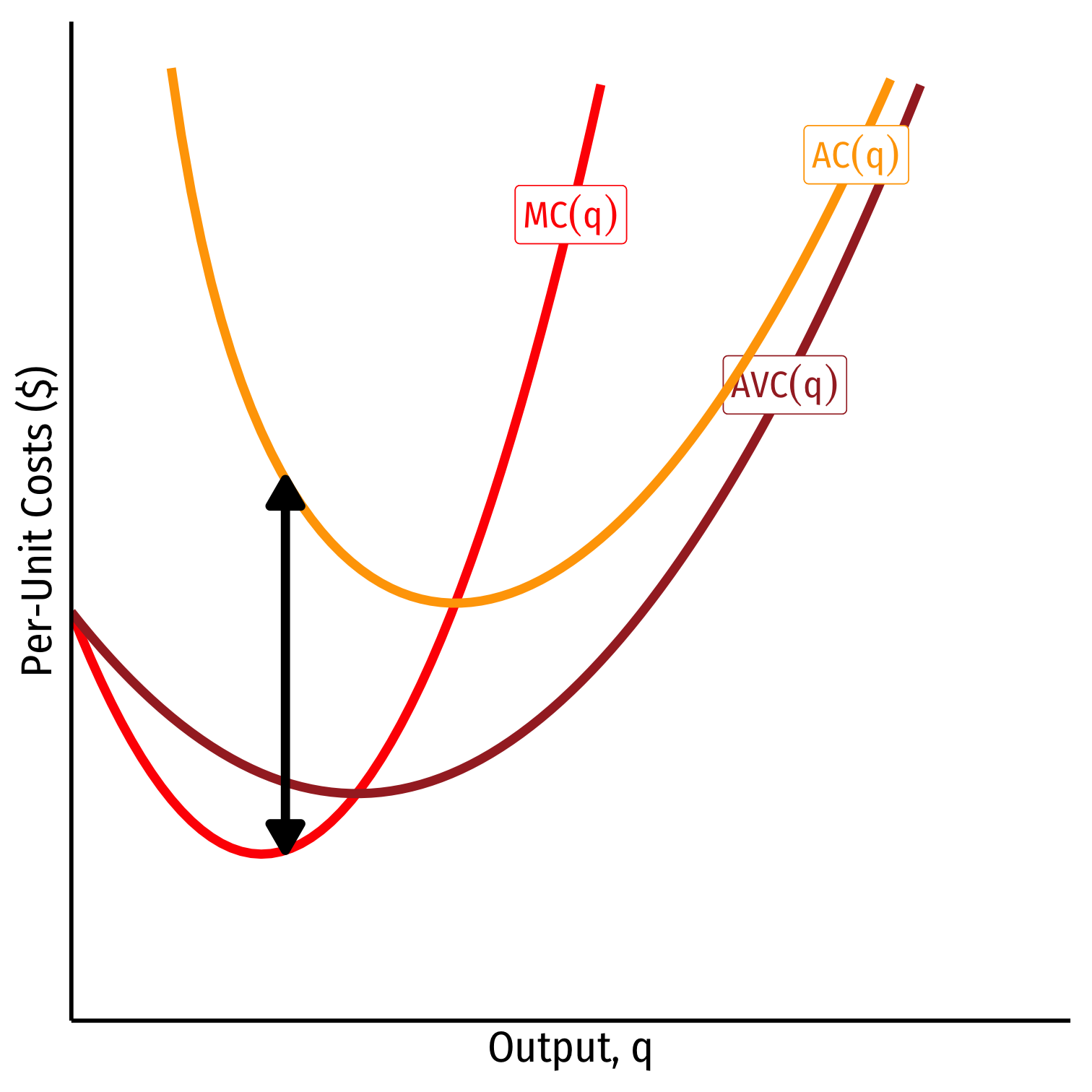

Relationship Between Marginal and Average

Mathematical relationship between a marginal & an average value

If marginal < average, then average ↓

Relationship Between Marginal and Average

Mathematical relationship between a marginal & an average value

If marginal < average, then average ↓

If marginal > average, then average ↑

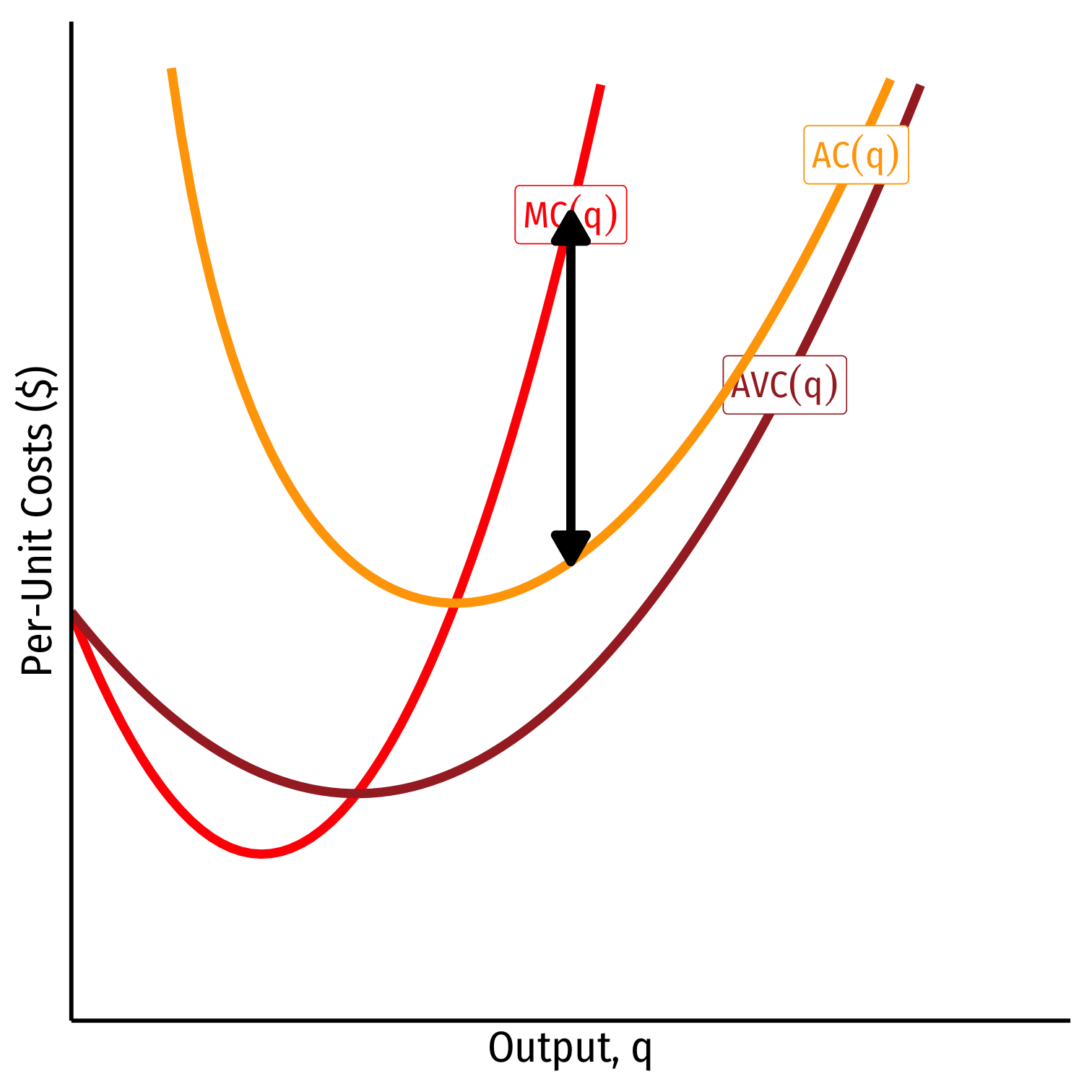

Relationship Between Marginal and Average

Mathematical relationship between a marginal & an average value

If marginal < average, then average ↓

If marginal > average, then average ↑

When marginal = average, average is maximized/minimized

Relationship Between Marginal and Average

Mathematical relationship between a marginal & an average value

If marginal < average, then average ↓

If marginal > average, then average ↑

When marginal = average, average is maximized/minimized

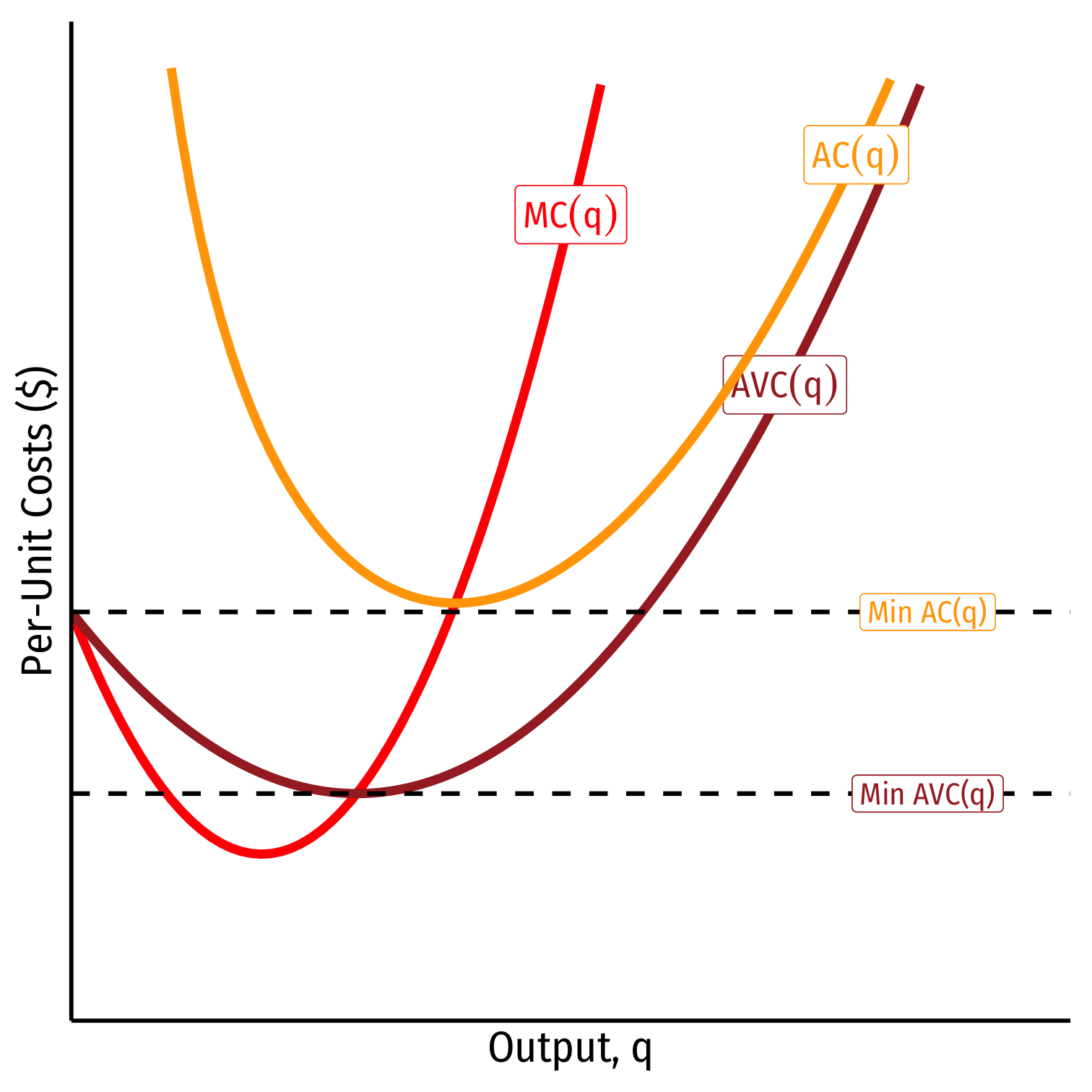

- When MC(q)=AC(q), AC(q) is at a minimum (break-even price)

- When MC(q)=AVC(q), AVC(q) is at a minimum (shut-down price)

Short Run Costs: Example

Example: Suppose a firm’s cost structure can be described by: C(q)=15q2+8q+45MC(q)=30q+8

Write expressions for the firm’s fixed costs, variable costs, average fixed costs, average variable costs, and average (total) costs.

Find the minimum average (total) cost.

Find the minimum average variable cost.

Costs: Example: Visualized

Costs in the Long Run

Costs in the Long Run

Long run: firm can change all factors of production & vary scale of production

Long run average cost, LRAC(q): cost per unit of output when the firm can change both l and k to make more q

Long run marginal cost, LRMC(q): change in long run total cost as the firm produce an additional unit of q (by changing both l and/or k)

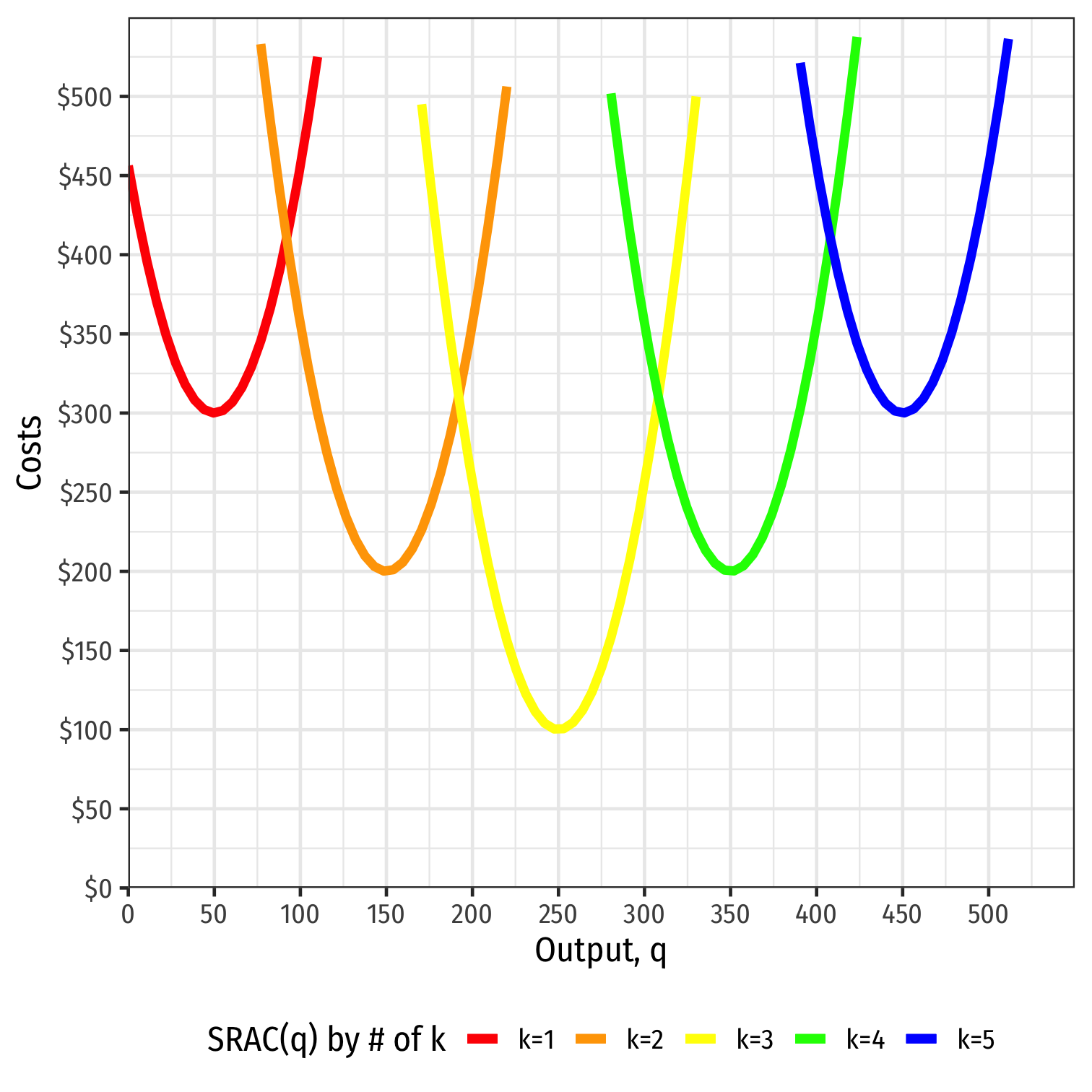

Average Cost in the Long Run

Long run: firm can choose k (factories, locations, etc)

Separate short run average cost (SRAC) curves for each amount of k potentially chosen

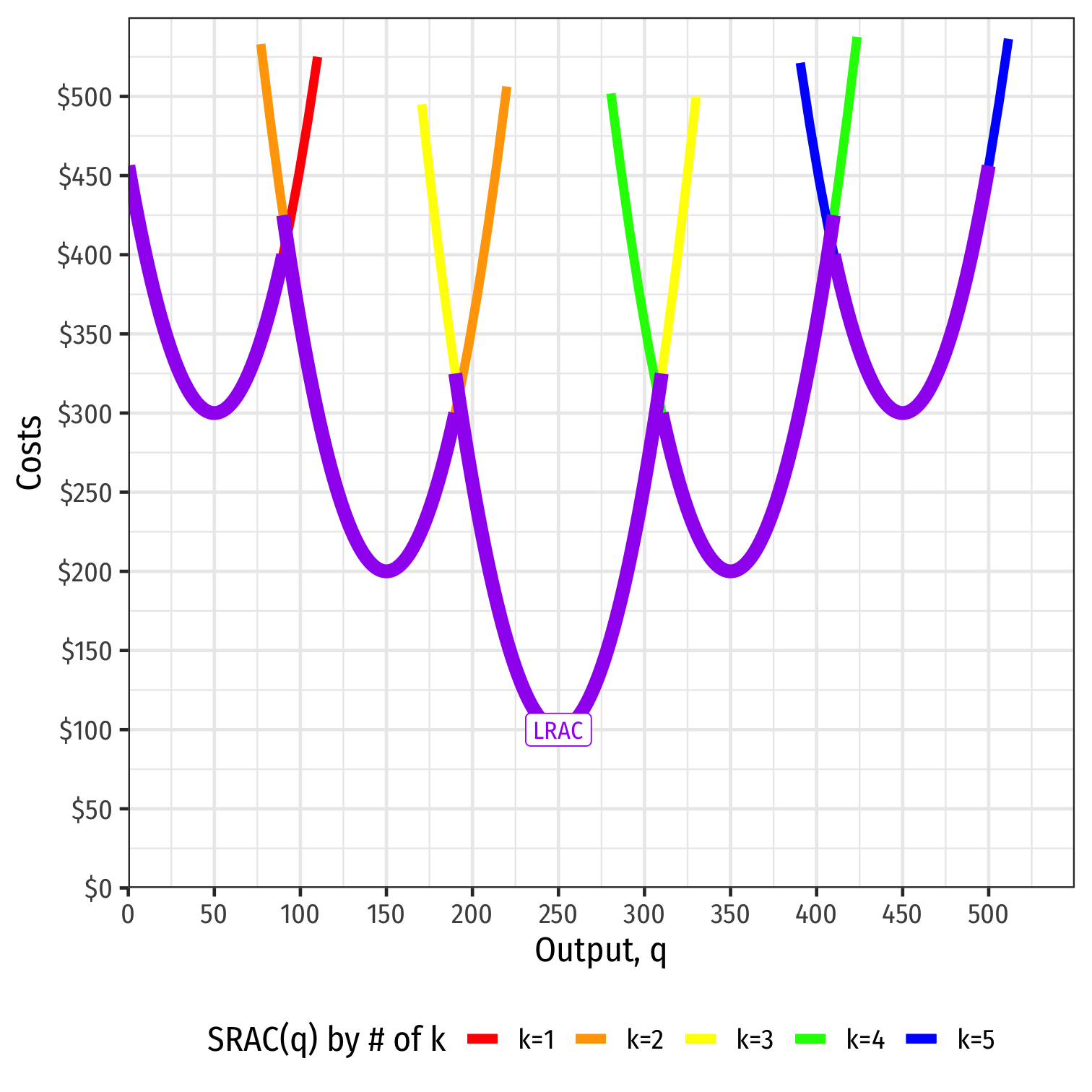

Average Cost in the Long Run

Long run: firm can choose k (factories, locations, etc)

Separate short run average cost (SRAC) curves for each amount of k potentially chosen

Long run average cost (LRAC) curve “envelopes” the lowest (optimal) regions of all the SRAC curves!

“Subject to producing the optimal amount of output, choose l and k to minimize cost”

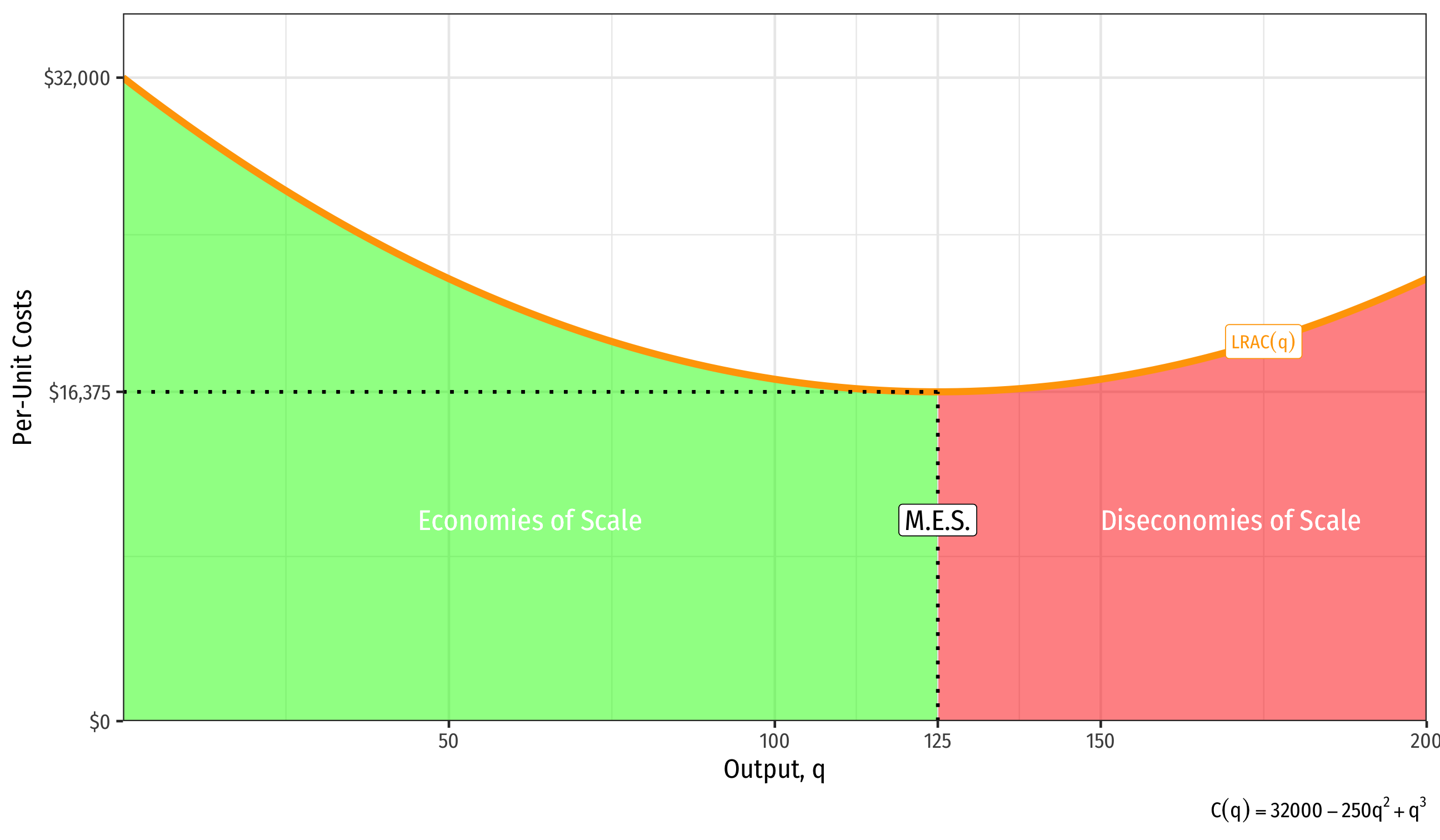

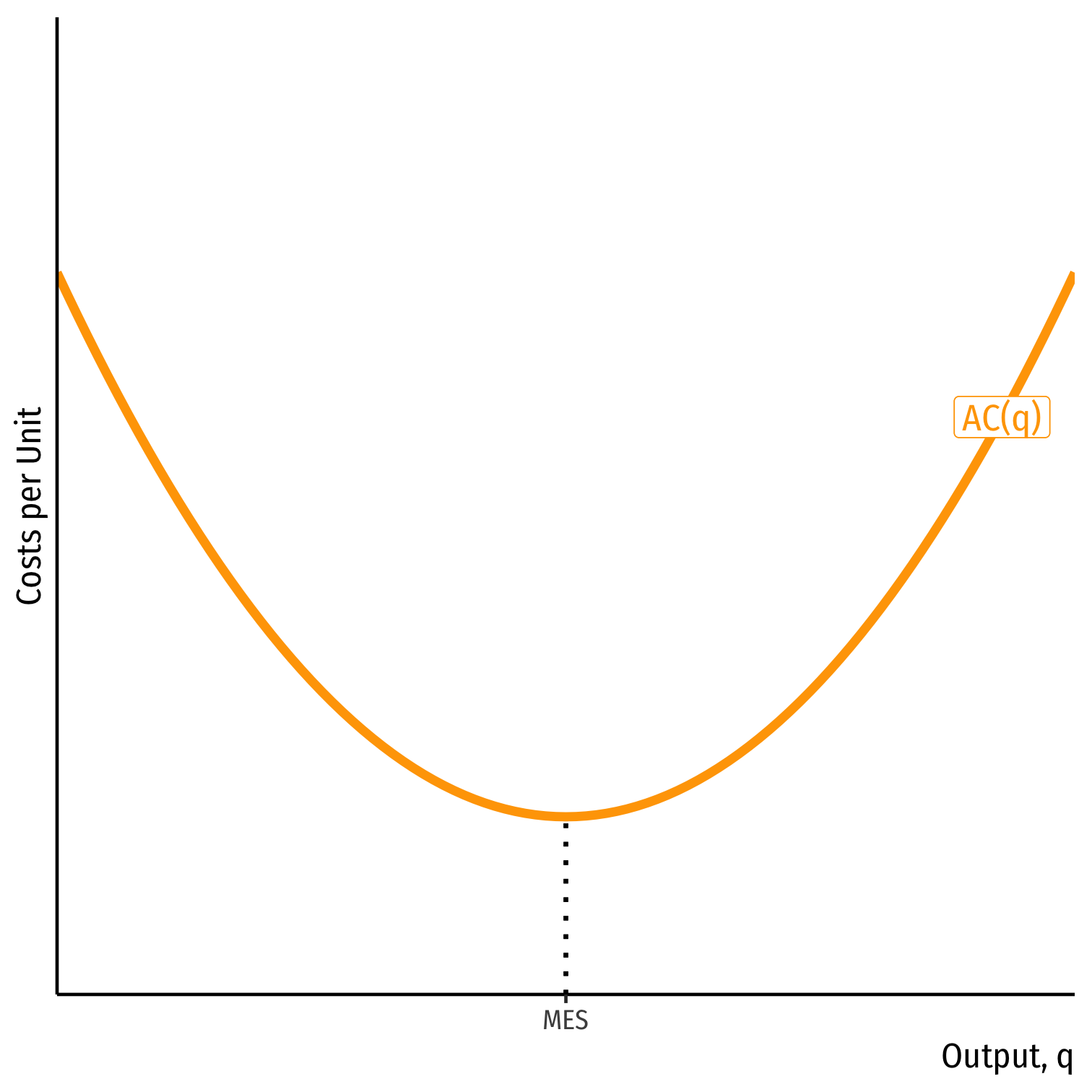

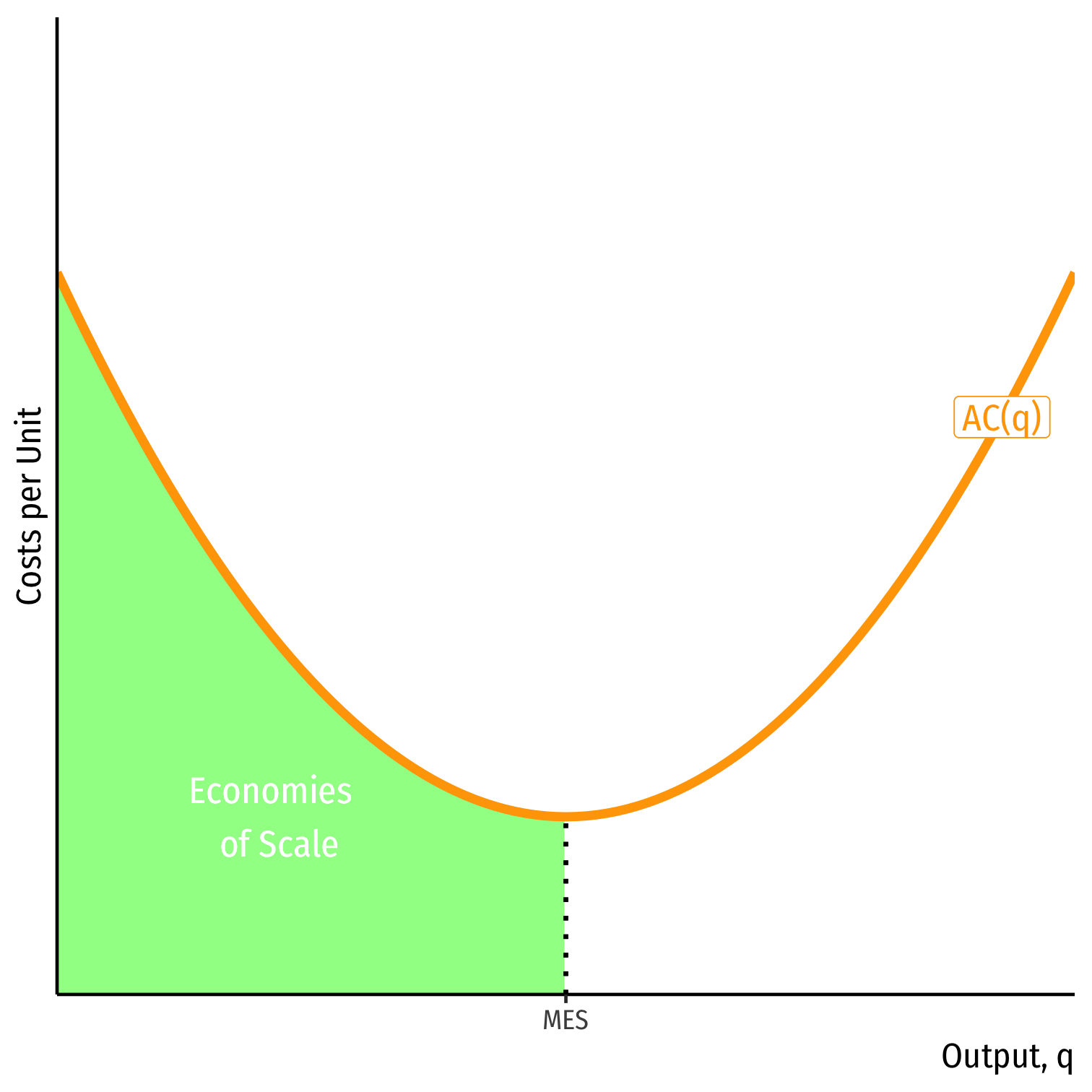

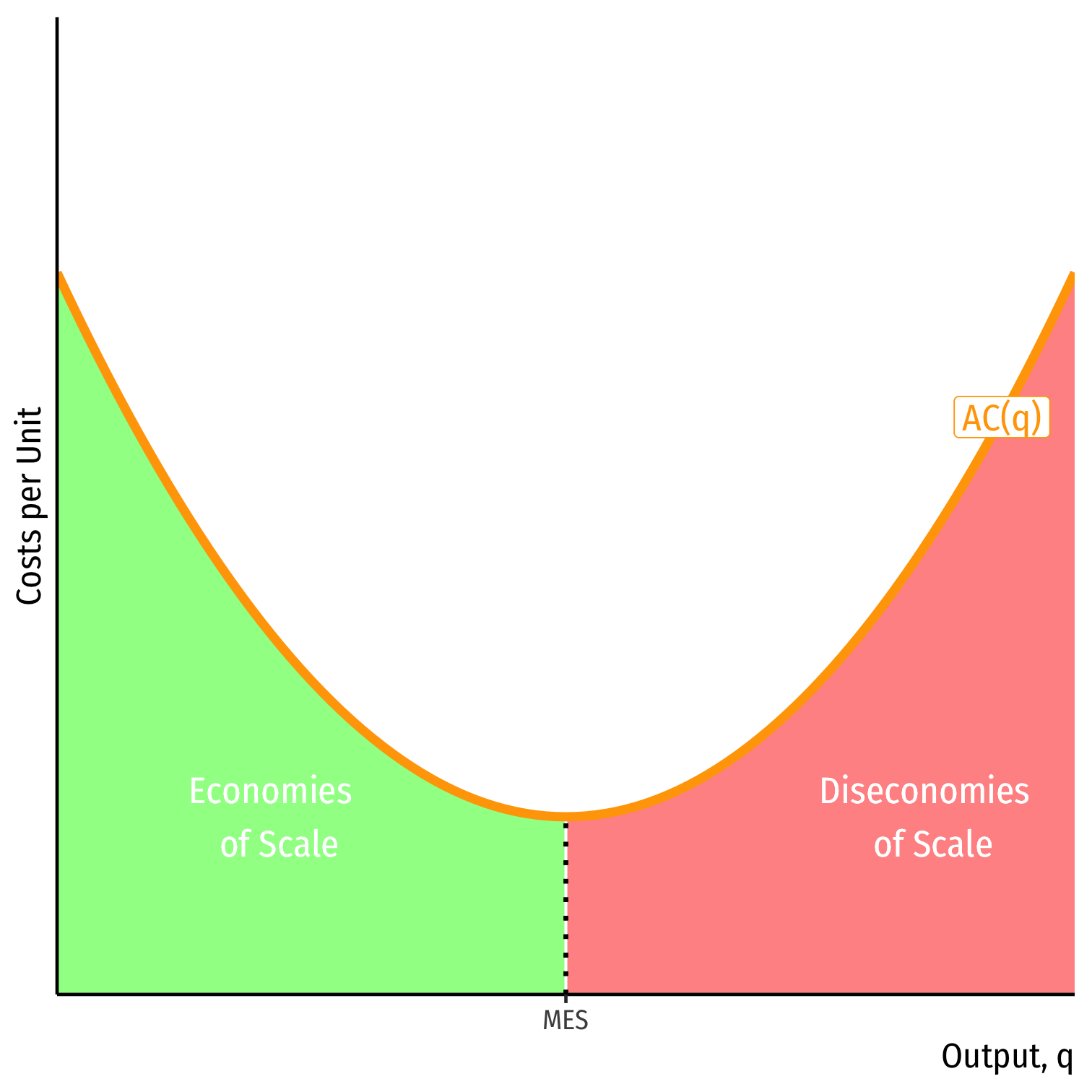

Long Run Costs & Scale Economies I

Further important properties about costs based on scale economies of production: change in average costs when output is increased (scaled)

Economies of scale: average costs fall with more output

- High fixed costs AFC>AVC(q) low variable costs

Diseconomies of scale: average costs rise with more output

- Low fixed costs AFC<AVC(q) high variable costs

Constant economies of scale: average costs don’t change with more output

- Firm at minimum average cost (optimal plant size), called minimum efficient scale (MES)

Long Run Costs & Scale Economies I

Note economies of scale ≠ returns to scale!

Returns to Scale (last class): a technological relationship between inputs & output

Economies of Scale (this class): an economic relationship between output and average costs

Long Run Costs & Scale Economies II

- Minimum Efficient Scale: q with the lowest AC(q)

- “optimal firm size”

Long Run Costs & Scale Economies II

Minimum Efficient Scale: q with the lowest AC(q)

- “optimal firm size”

Economies of Scale: ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Long Run Costs & Scale Economies II

Minimum Efficient Scale: q with the lowest AC(q)

- “optimal firm size”

Economies of Scale: ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Diseconomies of Scale: ↑q, ↑AC(q)

Long Run Costs and Scale Economies: Example

Example: A firm's long run cost structure is as follows:

LRC(q)=32000q−250q2+q3LRMC(q)=32000−500q+3q2

- At what levels of output will the firm face economies of scale and diseconomies of scale? (Hint: This firm has a U-shaped LRAC.)

Long Run Costs and Scale Economies: Example